First of all, thank you so much for inviting us into your chambers here in D.C., and for taking the time to sit down for this conversation.

Chief Judge Solomson:

It’s my pleasure. I’m happy to share a little of my story with the community. Fire away.

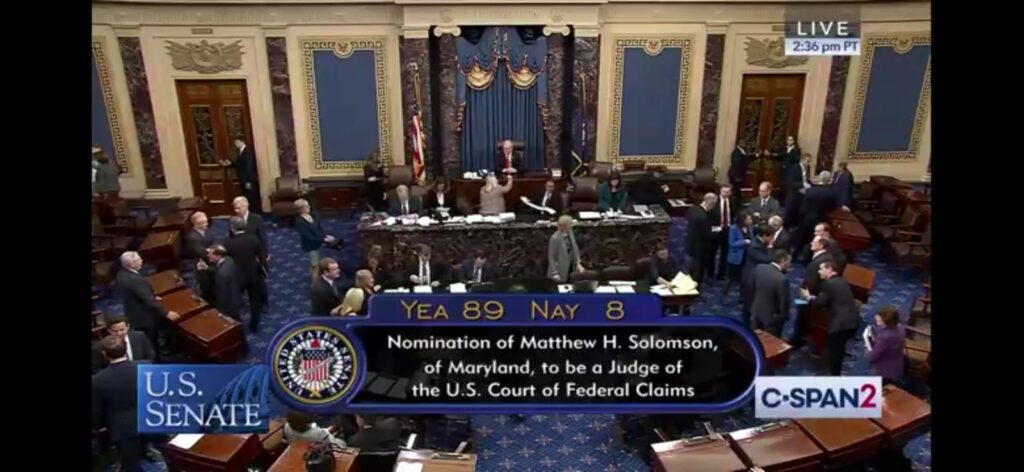

Chief Judge Solomson at his Senate confirmation hearing.

Let’s start from the beginning—how did you grow up, what was your education like, and how did you find yourself drawn to law?

I grew up all over the country as an Army brat. My father is a retired colonel and surgeon. By the time I reached eighth grade, I had already lived in nine different places: Louisiana, Texas, West Point, Silver Spring (once before), Savannah, San Francisco, Honolulu, Augusta (Georgia), and finally back to Maryland.

I went to public school here in the area, in Potomac. For college, I attended Brandeis, and by the end of 1995—just a month before my wedding—I didn’t have a job lined up. It was stressful. I had been interviewing in New York, Boston, Chicago, and here in DC, but with no luck. Lisa and I were getting married in three weeks and I had no job lined up. Although it’s really not my thing at all, I was spending Shabbos in Brookline (Boston) and went to the Bostoner Rebbe for a bracha for parnasa. I received a job offer from a large economics consulting firm back in D.C. later that very week (conclude what you will). That brought us to Silver Spring, and we’ve been here ever since (minus a half-year of yeshiva in Israel). Kemp Mill has been a wonderful community in which to raise our three kids. We have friends who are like family, and it’s been such a blessing to watch everyone’s kids grow up together. Our wonderful mechutanim also live around the corner – something we could never have foreseen when we first moved in. And my parents still live in Potomac.

So once you were back in the area, what path did your career take?

I knew that I wanted to apply to joint JD/MBA programs and those generally require work experience, so I worked at the consulting firm for a little more than a year. Once I applied and was accepted to a JD/MBA program, however, I left the firm, asked the school for a deferment, and took a year off to learn. We spent some time in Israel, and here at YGW as well.

After law and business school, my first job was clerking for a judge on the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, where I now serve as the Chief Judge. So my career has come full circle in a way that I could never have anticipated.

When it comes to managing a career, you can make plans, do everything “right,” and still have no idea where you’ll actually end up. When I started clerking here at the court, I couldn’t even tell you exactly what this court did. But I interviewed, received an offer, and accepted the position. At the time, I fully expected to go into patent litigation—that was my plan – and the judge for whom I clerked promised me the opportunity to work on patent cases with him. But when I joined my first firm after clerking — Arnold & Porter, one of the largest firms in D.C.—they steered me into work before the Court of Federal Claims, primarily focused on government contracts. At first I wasn’t thrilled about it, but over time I came to really enjoy the work and the completely unanticipated career path. It’s why I tell new lawyers to keep an open mind about what they want to do.

Chief Judge Solomson being sworn into office by then-Chief Judge Sweeney, with his wife Lisa holding the Chumash.

So I ended up building my career around the jurisdiction of the Court of Federal Claims, which includes not only government contracts, but also a wide-range of monetary claims against the United States government, including intellectual property, tax, employment, Fifth Amendment takings, amongst other types of claims. Eventually, I published a very thick and boring book about the court’s jurisdiction and that – combined with my experience in the private sector and the Justice Department – ultimately positioned me for the bench. It was a grueling, nearly three year process.I first interviewed with the White House for the judicial position in 2017, just after the inauguration, in April—right around Pesach. In fact, the initial interview date I was offered was on yuntiff and I considered trying to work it out rather than ask for a different date, but Lisa – who is always supportive – all but made me ask for another date. The White House had no problem with accommodating for unavailability for Pesach. Then, about a year later, on Purim, the White House called to say they would move forward with my nomination, assuming the background check went smoothly. The background check took a full year. Following the nomination, it was another few months before I had a Senate confirmation hearing and then approximately nine more months before I finally had a Senate floor vote.

What made you want to go through the interview process in the first place?

Sender, it was a complicated set of considerations. On the one hand, being a judge in the federal system is, I think, one of the highest honors you can have as a lawyer in this country. It’s also an opportunity to serve the country and play a vital role in the legal system.

One of my biggest regrets is not having joined the JAG Corps following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. I really wanted to join the Army as a lawyer, at least in the reserves. But with young children at home, it just didn’t seem like the life my wife had signed up for. Lisa had no objections, for the record. But I didn’t do it, and I regret that to this day. Now, I’m not trying to compare serving as a judge to serving in uniform—our armed forces put their personal safety at risk and often leave their families for long stretches of time—but being a judge is still a way to do some small part to serve my country. I’ve also always had a passion for the legal system itself. We have a fascinating, beautiful, and fundamentally just system in America. The chance to be part of it, to resolve cases, and to apply the law to new factual situations is both meaningful and enjoyable professionally. So I won’t claim it’s only about service. It’s also what I love to do—solving legal problems and helping to resolve disputes. And that’s a privilege in itself. Because what’s the alternative? In other systems or societies, people sometimes settle disputes through violence. In America, we have the rule of law—rules that are known in advance, applied by an impartial judge. Whether as a judge or as an attorney, whether in private practice or with the government, I think the practice of law is a noble profession and everyone who participates in the system is helping the country in a material way.

So when I got a call from a friend of mine—someone else who lives in Kemp Mill—proposing to recommend me to the White House for this judicial position, I said, “You’ll have my resume in five minutes.” And that’s how I wound up here. Of course, it was a very long process, and it didn’t happen without the help of many friends along the way. I am happy to share the hashgacha stories with you some other time.

The confirmation process sounds exhausting. What was it like going through such an intensive background check?

It really was crazy. The investigation went all the way back to my eighteenth birthday. At the time I started in the process, I was, perhaps, forty-three? I had to provide the FBI, the DOJ, and the Senate with every location I had ever lived, every job I had ever held. I had to provide a slew of professional references—including the names of opposing counsel from my cases—and copies of everything I had ever published.

Chief Judge Solomson leading Tehillim at a memorial service with fellow judges at Har Herzl.

I thought I had submitted a complete set of my work, but DOJ or the Senate staffers still dug up a letter to the editor of the Brandeis newspaper I had written in college—a piece I didn’t even remember. When they showed it to me, I acknowledged that it looked like my writing at that age, and that it had my friends’ names as co-signatories, but I insisted I had no recollection whatsoever of having written it. The letter had criticized my college newspaper for running an advertisement from a Holocaust denier. My point was simple: as a private newspaper, they didn’t have to accept such ads, and I couldn’t believe that the flagship newspaper of a Jewish-sponsored university like Brandeis would publish one. I asked the Justice Department lawyers, “Is this going to be a problem for me?” I worried someone might call it anti–free speech or something. They laughed and said, “Do you really think any senator is going to attack an Orthodox Jew for criticizing Holocaust denial? No one’s going near that with a ten-foot pole.” And they were right—it was never an issue.

But that shows how deep the process goes. The FBI talked to my neighbors, my parents, my friends—and then asked my friends for more names. Because we had spent six months in Israel, they even contacted the Israeli national police to confirm I had no criminal record in that country. That step alone added several months to the process. And of course I had no record there – I spent all of my time walking to and from yeshiva or doing Shabbos shopping in Geula.

Speaking of anti-semitism and universities, after October 7 you took to LinkedIn with a strong stand, refusing to hire law students who signed letters sympathetic to Hamas. How did you find the strength to do that?

It’s funny—when I was confirmed, I made perhaps two final thank-you posts on social media. One on Facebook for friends, and one on LinkedIn for professional colleagues. I announced I had been confirmed, thanked everyone, and essentially said, “This is the last you’ll see of me on social media. Everyone knows where to find me. Have a great life.” And I meant it. I stayed off social media almost completely—until October 7.

That day changed everything. I felt compelled to speak out. Reasonable people can disagree with that decision. Judges generally aren’t supposed to opine on controversial issues outside of their cases. But our ethics rules also encourage us to teach, to express opinions about the law and the profession, and to promote the rule of law and principles of justice. I thought it was important to address not only the terror attacks themselves, but also what they meant for the Jewish community in America. Within days—before Israel had even responded—you already saw anti-Israel protests. Really, anti-Jewish protests. On campuses, in New York City, and elsewhere.

Initially, what received a fair amount of press was my statement on LinkedIn that I would not hire as a law clerk any Harvard student who remained a member of the organizations that signed onto a pro-Hamas letter. If you resigned in protest, fine. But for students who stayed members of those groups, I argued they were not fit to be hired as Federal judicial law clerks, any more than would a student who expressed support for the KKK. Both the legal and mainstream press covered my statement.

Soon after, a number of major law firms—far more powerful than a single judge—began rescinding job offers to students who had signed or made pro-Hamas statements. Soon after, another judge, a friend of mine, followed suit with a similar statement.

Look, there’s a wide range of legitimate views about the Middle East. You can argue for two states, or whatever. That’s fine. But when you cross the line into supporting terrorism, that’s different. Free speech protects your right to say even very offensive things. But it doesn’t obligate me to consider you for a clerkship. And when protests move from speech into physical harassment—physically blocking Jewish students or intimidating them on campus—that’s not speech anymore. That’s prohibited conduct. And that’s exactly what we saw on a range of campuses.

After Harvard, you were also involved in the boycott of Columbia Law School. How did that come about?

I have hired law clerks from a range of law schools, including Harvard, UPenn, NYU, Georgetown, Notre Dame, Maryland, Cornell, Pepperdine, Fordham, Cardozo, and GWU. I pay attention to what is happening at law schools. At a certain point, what I was seeing at Columbia was intolerable. On my own, I knew I wouldn’t move the needle—if one judge says he or she won’t hire Columbia grads, no one cares that much. So I reached out via email to Judge Jim Ho of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and to Judge Lisa Branch of the Eleventh Circuit. Both had previously led boycotts of Stanford and Yale – refusing to hire their law students – after those schools mistreated conservative speakers and generally showed hostility to conservative students. Neither judge is Jewish.

Together, we concluded that a simple letter of condemnation wouldn’t change anything. The only way to get the university’s attention was a boycott. So thirteen or so federal judges, including myself, signed onto a statement saying we would not hire Columbia graduates going forward—starting with the incoming class, so prospective students had the chance to choose a different school. I published a Wall Street Journal op-ed explaining our decision. (Incidentally, it must’ve been Kemp Mill day at the Journal – my close friend Dr. Tevi Troy had an article published on the same page as mine.)

Some people argued that our hiring boycott would unfairly hurt innocent students, including Jewish students. But as Judge Ho explained, that critique is born of a loser mentality because it assumes failure. If you assume the boycott will succeed, that would mean the university has changed and reformed, and the boycott ends with a net positive result. And, indeed, Judge Ho is correct that if only thirty or forty judges had joined, the pressure would have been overwhelming, and the schools would have no choice but to change, and then no student would face any repercussions. So asking about innocent students makes a critical assumption that the boycott would not achieve its intended effect. All of those who signed the boycott had the attitude that we would succeed and perhaps more judges would join us.

Another final story on this is worth relating. Judge Ho called me later and said that his initial reaction to my email request was that this antisemitism issue was not his fight. After all, he had already taken a stand against Yale and Stanford, and caught flak for that. But then, he told me, he prayed on the matter one evening, and woke up thinking – and this brings me to tears every time I tell it – “what kind of person would I be if I only stood up for Christians and conservatives, and not my Jewish brothers and sisters.”

You mentioned that the boycott didn’t come without cost. What was the reaction like, and did you ever worry about security?

I think we’re tremendously blessed in this country. By and large, our fellow citizens support us, and that’s why America doesn’t look like some other places that seem to have been overrun by Hamas sympathizers.

But yes, the boycott drew criticism. Professors criticized us. Even some Jewish professors criticized us, calling it mean or unfair. And it wasn’t cost-free—we all faced ethics complaints (that ultimately were dismissed as meritless). But it was a small price to pay to help focus legal employers on the plight of Jewish students at Columbia. As for security—yes, it’s always a concern. Judicial security is an important issue. There’s always someone who loses in court, which means there’s always someone unhappy with you as a judge. In fact, if you look at recent years, Congress has been grappling with this very problem. One Federal judge in New Jersey, Judge Salas, was the victim of a serious crime – an evil man who I believe once had a case before her, came to her home, shot her husband, and killed her son. And I think that some (if not all) Supreme Court justices today need around-the-clock security due to threats. So yes, it’s definitely something we think about.

I heard that after October 7 you even brought Rabbi Frank in to speak at the court. How did that come about?

Yes. In the aftermath, a number of Jewish colleagues—both inside the court and lawyers I knew outside—felt this real need to connect with other Jews, to connect more deeply with Judaism, and to process what had happened and what we were experiencing in the Diaspora. I think we were all feeling that need, no matter our observance level. October 7 was like a pogrom out of old-world Europe—or like Chevron in 1929—only carried out in our time. When you stop and scale the numbers, if the same thing had happened here in the United States, it would have been the equivalent of something like 40-50,000 people murdered in a single day. It’s unfathomable.

Because of that need, I invited Rabbi Frank to come in and speak to a group of judges and lawyers who expressed interest in getting together. It was a very diverse group of Jews—I think he remarked that it was the most diverse group he’s ever addressed. We actually brought him in twice, and the feedback was incredible. People said it was sensitive, thoughtful, and exactly what they needed. In fact, I think one of those shiurim ended up being his most downloaded from his podcast library. We’ve talked about doing it again and I’ve had others ask about it. It’s been a while now, so maybe it’s time to regroup.

And what about being an openly observant Jew—has that ever posed unique challenges for you on the bench?

Not at all. Honestly, it was more of a challenge in private practice. When you’re a young lawyer, you have to explain Shabbos and yom tov to every new boss. Or you’re out to eat with colleagues, sipping a Diet Coke and eating cold fruit while they’re eating burgers, and it can feel awkward.

As a judge, though, I set the schedule. And I have the luxury of being able to close chambers for Jewish holidays—and out of respect, I do the same for my non-Jewish clerks between December 24 and January 1. I’ll work from home, but they get that time off.

Before my Senate confirmation hearing, I asked a DOJ lawyer helping us nominees through the process whether it would be a problem for me to wear a yarmulke at the hearing. He said, “Not with our side of the aisle—and we have all the votes.” Funny answer. I was confirmed by a very wide margin, so nobody was too troubled by my religious observance.

Do you have any memorable experiences explaining your observance to employers before becoming a judge?

One of my favorite stories goes back to when I received a job offer at a company. I had a standard spiel I’d give to every potential new boss. I’d say: “I’m a Saturday Sabbath observer. From Friday evening until Saturday night, I’ll be completely out of pocket—no phone, no email. But I’ll pick up the work Saturday night, I’ll answer emails every night before bed and first thing in the morning, and I’ve never dropped the ball. If this is a problem for you or the company, that’s fine—just let me know now. I won’t sue or complain about discrimination. I just want this to be a good fit.”

One boss—now a good friend—told me it wouldn’t be a problem. But on my very first Wednesday, he came into my office and said, “Don’t you have to be getting home?” I replied, “Why would I need to get home?” He shrugged and said, “Well, it’s getting dark out.” I said back “So?” “Your Sabbath?,” he asked. I realized he thought I had to be home every night before dark. I laughed and explained, “The Jewish Sabbath starts Friday night and ends Saturday night. I don’t need to leave early today.” He just shook his head and said, “Whatever, man,” and walked out. He literally didn’t know when Shabbos was. That’s a common thing I warn young professionals about – outside of NY or LA, people aren’t familiar with Jewish observance or, say, yarmulkes.

That’s hilarious—but did you ever feel it was a challenge to maintain observance in the workplace?

I never really had an issue. Sometimes you do have to work harder to show you’re not slacking. But if you do great work, if you’re responsive and deliver high-quality results, people respect that. They’ll be respectful of your religious commitment and the fact that you’re offline on Shabbos or yom tov.

But you absolutely can’t coast and expect special treatment. You’ve got to set the bar high, because in the middle of a litigation deadline, when everyone else is working around the clock, you may need to say, “Sorry, I’m out for three days.” And of course, people don’t understand that you’re not at the beach. On Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur, you’re in shul twelve hours a day, or fasting—but nobody cares. To them, you’re just unavailable and on vacation. And you can’t expect sympathy. You just make it work, and you make up for it by being excellent and fully committed the rest of the time. I also always offered my non-Jewish colleagues to cover for them during the Christmas season or around Easter.

Sometimes people assume that being an Orthodox Jew must affect how you approach the law. How do you think about that intersection?

It’s important to separate between two very different things: halacha and skills from learning.

Halacha has nothing to do with the substantive answers to American legal questions. My oath is to uphold the Constitution and to faithfully apply American law. Above me in the judicial hierarchy, I have the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and, of course, the United States Supreme Court. My role is to faithfully apply to cases the statutes Congress passes (and the President signs into law), the regulations the Executive Branch promulgates, and the binding decisions of the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court.

It’s hard to even think of an issue in my court where halacha would have a view, but if you asked, what if halacha conflicted with American law in a case before you?—the answer is simple. I would apply American law. Period. My oath and duty require me to apply American law. If halacha ever conflicted with American law, my duty would still be to apply American law. If I ever felt I could not fulfill my oath to do so, for whatever reason, I would resign. That’s the deal. Other religious judges — including a sitting Catholic Supreme Court justice — have essentially been asked this kind of question, and to me it reflects a subtle anti-religious bias. Nobody asks a secular judge what happens if the law conflicts with their secular humanist philosophy as if it’s not essentially a religion. In any event, my answer is that my religious views stay outside the courtroom.

What about the skill set from learning in yeshiva—does that translate into your work as a judge?

That’s a different story. Yeshiva provides a kind of legal training in its own right. You do case analysis, close reading of texts, and you apply rules to new factual scenarios. That’s excellent preparation for law school. At the same time, law school also teaches things yeshiva doesn’t—structured theory, legal vocabulary, and different frameworks for interpretation.

For example, in American law, there are at least three approaches to interpreting a statute, for example:

- Textualism – sticking closely to the plain, original public meaning of the words of a binding text like a statute or constitutional provision.

- Purposivism – looking to the broader purpose of the law, even if it pushes beyond the text.

- Intentionalism – focusing on what Congress specifically intended, sometimes based on congressional committee reports or debates.

When I was learning Yoreh De’ah, I sometimes noticed that one authority might be more sensitive to specific language and word choices, another to the broader purpose of a rule, and another to a related text elsewhere. It struck me that some poskim were essentially doing “textualism” while others were “purposivists,” etc. – even that vocabulary isn’t used. But that’s my point – in my experience, the beis medrash isn’t focused too much on legal theory or methodology (even in the context of halacha).

And you’ve kept up your learning alongside your legal career?

Well, I’ve tried, but admittedly some periods of my professional life have been more productive than others in terms of Torah learning. A few years ago, however, my son encouraged me to pick up something more challenging that would motivate me. And so I applied and was accepted to the yadin yadin kollel program at YU/RIETS. The learning is self-study, and it takes about four years, I understand, to complete the basic curriculum. We have weekly chaburas via Zoom and in the several past years I have attended the chabruas at RIETS in person (thanks to Amtrak). In addition to bechinos, another requirement is that we must present a chabura once per year. I’ve completed two thus far (available on YUTorah) and it is likely the most challenging, most intimidating thing I have ever done – more so than appearing before an appellate court or the Senate. I am not exaggerating even a little. The Roshei Kollel – including HaRav Mordechai Willig, HaRav Yona Reiss, and HaRav J. David Bleich – typically attend, as do the other chavrei kollel, all of whom are, of course, tremendous talmidei chachamim. It is a tough crowd. My goal is limited – not to embarrass myself.

In 2024, you joined a delegation of judges on a trip to Israel. Can you tell me about that experience?

Yes. A group of three other Jewish judges and I organized it—14 federal judges in total, evenly split: seven Jews, seven non-Jews; seven appellate judges, seven trial judges. The World Jewish Congress sponsored the trip, and it lasted four or five days.

We met with Supreme Court justices, Knesset members, Israeli State Department lawyers arguing Israel’s case at the ICC, and military lawyers and generals. But we also went south. In Kibbutz Be’eri, we were guided by a chayelet who had lost a handful of family members on October 7. She walked us through their homes, through the devastation, and shared her story with extraordinary gevurah. I honestly don’t know how she did it without breaking down. For the rest of us, it was overwhelming.

We were also shown a 47-minute video of the atrocities – the one that hasn’t been released publicly (phones weren’t allowed in the room). The footage was horrific. Everyone came out shaken; some sat in silence, others cried openly. It was, without question, one of the most emotional moments of my life.

It was a great privilege—and very emotional—to stand together, to meet hostage families, and to bear witness to the atrocities. I think every judge who joined us on the trip has since spoken to law school groups about October 7, our experience in Israel, and what we learned there.

As we enter the High Holidays, do you have a message for the community?

My wife Lisa always reminds me – correctly – that the holidays are a chance to take a beat to be grateful … to express gratitude to our Creator for our lives and to appreciate the opportunity to spend meaningful time with our family and friends (who are like family), while also reflecting on what makes life meaningful. It’s a chance to rebalance our priorities for the upcoming year. We in Kemp Mill are indeed very lucky to live in such a special community with special friends and neighbors. I don’t think I’m in a position to offer a message, but I’d say that everyone should try to appreciate the time you have with the people you love and don’t wish the time by. Even if you’re young, and work (with the Jewish holiday season) feels very difficult – something I remember – it all goes by quickly and you can’t get the time back.